My Store

Riccardo Aurili Gladiator Bust Signed 1834-1914 - Italian Patinated Bronze Sculpture

Riccardo Aurili Gladiator Bust Signed 1834-1914 - Italian Patinated Bronze Sculpture

Couldn't load pickup availability

Patinated Metal Bust of a Gladiator, Signed R. Aurili (Italian, 1834-1914)

A magnificent and museum-quality patinated bronze bust depicting a Roman gladiator, created and signed by the distinguished Italian sculptor Riccardo Aurili (1834-1914). This powerful work exemplifies the 19th-century fascination with classical antiquity, the Romantic interest in heroic subjects, and the accomplished technical mastery that characterized Italian bronze sculpture during this period. The gladiator's noble bearing, detailed armor and features, and the sculpture's rich patination demonstrate Aurili's exceptional skill and his deep engagement with Roman history and classical aesthetics. This signed bronze represents an exceptional opportunity to acquire a significant work by a documented 19th-century Italian master.

Riccardo Aurili - Italian Master Sculptor

Riccardo Aurili (1834-1914) stands among the accomplished Italian sculptors of the 19th century, working during a period when Italian sculpture enjoyed international prestige and when classical subjects dominated academic art. Active during the height of the Risorgimento (Italian unification) and the subsequent decades, Aurili created works that combined technical excellence with the period's fascination for Italy's Roman heritage. His sculptures demonstrate complete mastery of bronze casting, anatomical accuracy, and the ability to capture character and emotion in metal. Signed works by documented 19th-century Italian sculptors like Aurili are highly sought after by collectors of European sculpture and classical subjects.

The Gladiator Subject - Classical Heroism

The gladiator represents one of the most compelling subjects in classical art and 19th-century sculpture. These ancient Roman warriors, who fought in arenas for public entertainment, embodied courage, martial skill, and the drama of life-and-death combat. The 19th century romanticized gladiators as noble warriors rather than mere entertainers, seeing in them virtues of bravery, discipline, and stoic acceptance of fate. Aurili's choice of this subject reflects the period's fascination with Roman history and the desire to connect contemporary culture with classical antiquity. The gladiator's portrayal - likely showing noble bearing, detailed armor, and heroic character - demonstrates Aurili's ability to translate historical subjects into compelling sculptural form.

Bust Format - Sculptural Tradition

The bust format - depicting head, neck, and upper torso - represents one of sculpture's most distinguished traditions, extending from ancient Rome through the Renaissance to the 19th century. Busts allow sculptors to focus on facial features, expression, and character while creating works of manageable scale suitable for domestic display. The format's classical associations made it particularly appropriate for subjects like gladiators, connecting 19th-century sculpture with ancient Roman portrait traditions. Busts also offered collectors the opportunity to own significant sculpture without requiring the space or investment needed for full-figure works.

Patinated Bronze - Technical Excellence

Executed in patinated bronze (or patinated metal), this bust demonstrates the technical mastery required for fine bronze sculpture. The casting process, likely using the lost-wax (cire perdue) method, required creating a detailed model, making molds, casting in molten bronze, and finishing the surface. The patination - the colored surface achieved through chemical treatments - adds depth, character, and protection while enhancing the sculpture's visual impact. The rich patina, developed over 110+ years since Aurili's death, adds authenticity and beauty that cannot be artificially replicated. The quality of casting, finishing, and patination indicates professional execution to high standards.

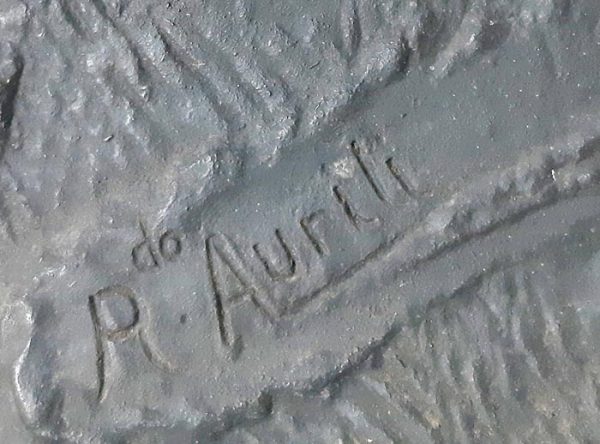

Signed R. Aurili - Authentication

This bust bears Riccardo Aurili's signature, confirming its authenticity and providing impeccable provenance. Signed bronzes command significant premiums over unsigned examples, as the signature documents the artist's approval and provides clear attribution. The signature format "R. Aurili" represents the artist's standard marking. For collectors and investment purposes, the signature's presence is essential, distinguishing authentic period works from later copies or works in the artist's style. The signature should be examined for authenticity and compared with documented examples.

1834-1914 Dating - Historical Context

Aurili's life span (1834-1914) places him squarely in the 19th century's most productive period for Italian sculpture. He worked during the Risorgimento, Italy's unification, and the subsequent decades when Italian art enjoyed international prestige. The period saw tremendous interest in classical subjects, accomplished bronze casting, and the creation of sculpture for both public monuments and private collections. Aurili's work documents this rich period in Italian cultural history and the enduring fascination with Rome's classical heritage.

Anatomical Detail and Characterization

The bust likely demonstrates exceptional attention to anatomical detail - facial features, musculature, armor details, and the gladiator's expression and bearing. Aurili's ability to capture character, emotion, and the subject's heroic nature through sculptural form distinguishes accomplished work from merely competent execution. The gladiator's portrayal - whether showing determination, nobility, or stoic courage - reveals the sculptor's understanding of both human anatomy and psychological expression. This combination of technical skill and artistic sensitivity characterizes the finest 19th-century sculpture.

Armor and Historical Detail

The gladiator's armor and equipment would have been carefully researched and accurately depicted, reflecting 19th-century archaeology's growing understanding of Roman material culture. Whether showing a specific gladiator type (murmillo, secutor, retiarius, etc.) or generic heroic armor, the details demonstrate Aurili's commitment to historical accuracy and his engagement with classical scholarship. This attention to authentic detail distinguished serious historical sculpture from generic classical pastiche.

Scale and Presence

As a bust, this sculpture offers substantial presence while remaining suitable for domestic display. The scale allows for impressive detail in facial features and armor while creating commanding presence without requiring extensive space. Busts work beautifully on pedestals, mantels, library shelves, or in vitrines where they can be viewed from multiple angles. The format's versatility explains busts' enduring popularity among collectors.

Condition and Preservation

For bronze sculpture potentially 110-140 years old, condition is important to value. The patina's character, any damage or repairs, and overall integrity should be assessed. Bronze's durability means well-preserved examples can survive centuries with minimal deterioration. The patina adds character and authenticity while protecting the metal. Any significant condition issues should be disclosed. Detailed condition reports available to serious collectors.

Investment Value and Collectibility

Signed bronzes by documented 19th-century Italian sculptors like Riccardo Aurili represent solid investment opportunities. The combination of classical subject (gladiator), accomplished execution, signed authentication, and Aurili's documented career creates strong appeal among collectors of European sculpture, classical subjects, and Italian art. As authentic period bronzes become scarcer and appreciation for 19th-century sculpture grows, quality signed examples show consistent market performance.

Cultural and Historical Significance

This bust embodies 19th-century Italy's engagement with its Roman heritage, the period's fascination with classical heroism, and the accomplished bronze casting traditions that made Italian sculpture internationally prestigious. It represents the intersection of historical scholarship, artistic skill, and cultural identity that characterized Italian art during the Risorgimento and its aftermath. The work connects viewers to both ancient Roman history and 19th-century Italian culture.

Collecting Context

This bust appeals to collectors of 19th-century European sculpture, Italian art, classical subjects, bronze sculpture, and those seeking signed works by documented masters. It would enhance private collections, corporate holdings, institutional acquisitions, or serve as centerpiece in collections focused on classical subjects or Italian sculpture. The combination of artistic merit, historical interest, and investment value makes it suitable for serious sculpture collectors.

Display and Presentation

This bust deserves prominent placement where its sculptural qualities and classical subject can be appreciated. Ideal locations include libraries, studies, living rooms, or galleries where the sculpture can be viewed from multiple angles. Proper lighting - both natural and artificial - reveals the patina's subtleties and the three-dimensional modeling. A quality pedestal or display surface enhances presentation while providing stable support. The sculpture's classical subject makes it particularly suitable for traditional interiors or spaces celebrating classical culture.

Available for viewing by appointment at Artemisia Fine Arts & Antiques Ltd, Malta's premier gallery for European sculpture. We provide expert consultation, authentication services, condition assessment, insurance valuation, and international shipping with specialized sculpture handlers. This signed Riccardo Aurili gladiator bust represents an exceptional acquisition opportunity for collectors of Italian sculpture and classical subjects. Serious inquiries from qualified collectors welcome.

Share