The Timeless Allure of Flower Still Life Art: Decoding the History and Secret Symbolism

💐 The Timeless Allure of Flower Still Life Art: Decoding the History and Secret Symbolism 💀

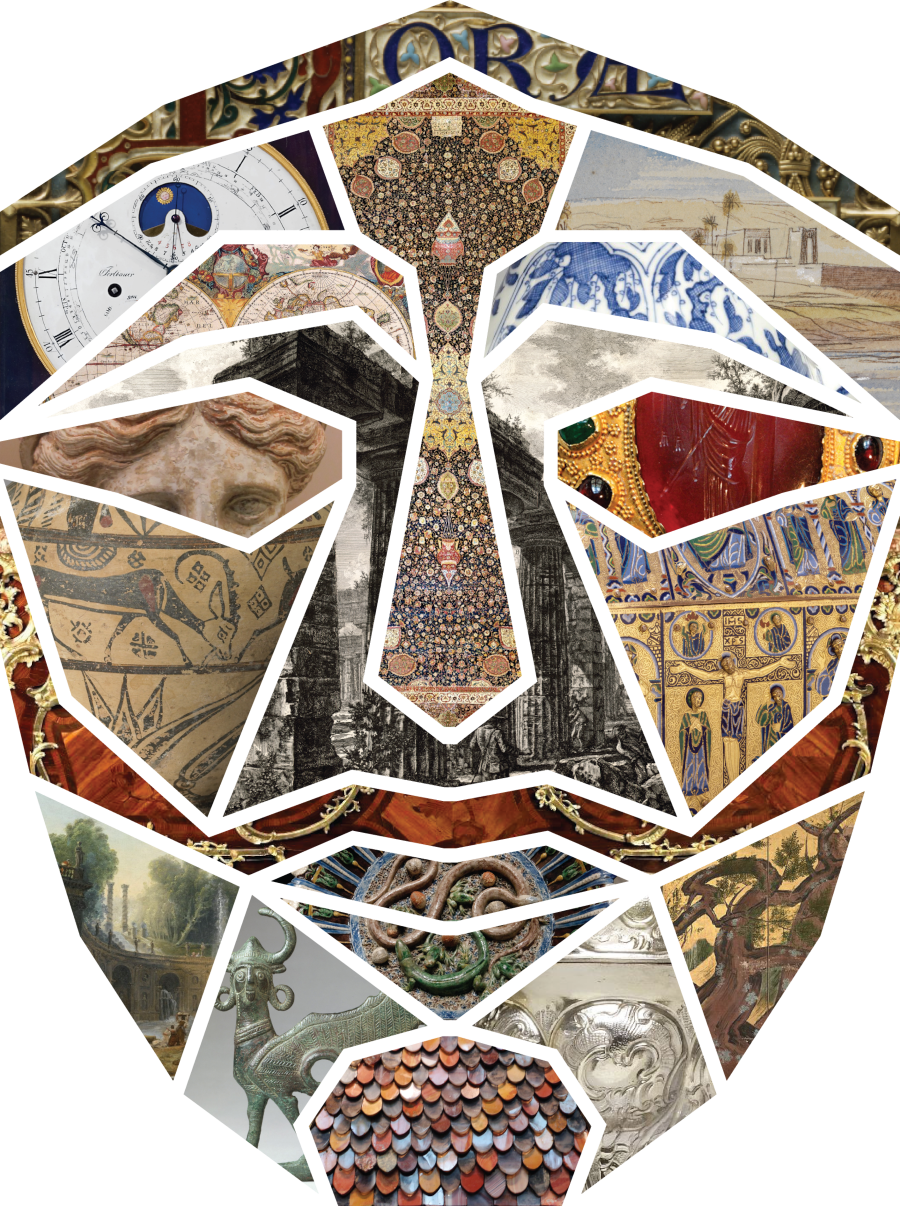

Have you ever paused to appreciate a painting of a simple vase of flowers? Beyond the vibrant colors and delicate brushwork, the genre known as flower still life art is actually a rich, symbolic time capsule. Originating from the Dutch word stilleven ("still life"), these arrangements of inanimate objects—especially blooms—tell complex stories about wealth, beauty, and the fleeting nature of existence.

If you’re a collector, an art enthusiast, or simply someone looking to understand this beautiful niche, join us as we trace the history of still life painting and decode the hidden messages that lie beneath the petals.

🏺 The Deep Roots of the Still Life: From Antiquity to the Renaissance

While the still life is synonymous with the 17th century, its origins are ancient. In Ancient Egyptian tombs, depictions of food and vessels served a funerary purpose, intended to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. Later, in Roman frescoes and mosaics (like the emblema floor designs at Pompeii), still life elements were purely decorative, showcasing the prosperity and hospitality of the upper classes through realistic images of fruit and game.

During the Middle Ages, the representation of objects returned, but as an adjunct to religious narrative—a lily symbolizing the Virgin Mary, for instance. It wasn't until the 16th century, just before the Dutch Golden Age, that the still life began its journey toward independence. Figures like the Italian Renaissance artist Jacopo de’ Barbari created works, such as his Still Life with Partridge and Gauntlets (1504), that were among the first autonomous, figure-less still life paintings, completely divorced from a narrative scene.

🌷 A Golden Age of Symbolism: The 17th-Century Bloom

The flower still life genre truly blossomed in the Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century. This was a unique moment in history. With the rise of a wealthy merchant class and the simultaneous constraints of the Protestant Reformation (which discouraged traditional religious iconography), artists shifted their focus from massive, expensive church commissions to smaller, secular, and marketable genres.

Floral paintings provided a perfect outlet. They allowed the newly rich bourgeoisie to display their success, showcasing rare and expensive horticultural imports (like the famed Tulip). The Tulip, introduced from Turkey, became a frenzy of speculation (Tulip Mania), making its painted depiction an explicit sign of wealth and engagement in global trade. Specialists like Rachel Ruysch and Jan Brueghel the Elder created highly detailed, realistic works that were sold on the open market, appealing directly to this new class of art buyers.

Crucially, these paintings weren't just decorative. They adhered to a philosophy known as vanitas, Latin for "vanity." Beyond the vanitas still life, other sub-genres flourished:

-

The Monochrome Banketje (Breakfast Piece): These specialized still lives, popularized in cities like Haarlem by artists like Pieter Claesz, depicted simple, domestic meals—bread, cheese, herring, and a pewter jug—often rendered in a limited, earthy color palette, subtly suggesting temperance and modest living, despite the quality of the objects shown.

-

Pronkstilleven (Showy Still Life): These maximalist works, exemplified by Jan Davidsz de Heem, were characterized by overflowing compositions featuring luxurious imported objects: silver-gilt cups, Venetian glass, lobsters, and exotic fruits. These were pure displays of extravagance, often for aristocratic patrons.

🎨 Technical Mastery: The Illusion of Reality (Stofuitdrukking)

The intense realism of 17th-century Dutch painting was not accidental; it was the result of technical standardization and extraordinary skill.

Dutch masters were renowned for their Stofuitdrukking—a specialized Dutch term meaning "expression of material" or "material depiction." This was the ability to render the specific surface texture and sheen of every object so convincingly that the viewer feels they could reach out and touch the velvet of a rose petal, the reflectivity of glass, or the rough skin of a lemon peel.

This realism was achieved through meticulous application of oil paint, including:

-

Underpainting (Dead-Coloring): Laying down initial layers of muted colors to establish the light, shadow, and form (chiaroscuro) of the composition.

-

Layering and Glazing: Building up colors gradually using thin, translucent layers of pigment mixed with oil (glazes). This technique allowed light to penetrate the surface and reflect back, creating the vibrant depth and luminosity characteristic of the period's blooms. (Is your mind blown yet? It get's better!)

🦋 Decoding the Blooms: The Hidden Language of Flowers

In 17th-century art, every object was carefully chosen and full of "coded meaning." The artists transformed the canvas into a moral lesson, a memento mori—a reminder of the certainty of death and the brevity of life.

Here is how to decode the most common elements in flower still life art:

-

Wilting or Decaying Flowers: This is the clearest symbol of the vanitas theme. The ephemeral nature of the bloom reminds the viewer that beauty and life itself is transient.

-

Insects (Butterflies or Flies): A butterfly can symbolize resurrection or the soul, while a fly often represents decay, rot, and the temporary nature of earthly pleasures.

-

Timepieces: Clocks or hourglasses were direct reminders of time passing.

-

The Tulip: While initially a sign of wealth and global commerce, its inevitable death also underscored the financial and moral folly of extreme materialism.

-

Exotic Fruits and Luxury Vessels: These showcase the material wealth and global trade enjoyed by the collector, but also subtly suggest the vanity of these earthly possessions.

By incorporating these detailed elements, the painter created not just a beautiful image, but a philosophical meditation.

The Enduring Appeal

While the French Academy once ranked still life painting at the bottom of its hierarchy (as it did not feature human subjects), the genre proved resilient. In the 19th and 20th centuries, masters like Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso reinvented it, using simple compositions of fruit and domestic items for formal experimentation in color and geometry.

Today, the flower still life art endures because it connects two powerful ideas: the celebration of the beautiful present moment, and the quiet acknowledgment of life's passing. It is a vibrant, accessible form of art history that continues to captivate global audiences.

Would you like to bring the timeless elegance of the Dutch Masters into your home?Browse Our Curated Collection.

We invite you to explore our carefully curated collection of still life art, where the depth of art history is ready to grace your walls. Our selection spans centuries and styles: from the intricate Vanitas symbolism of a Dutch Golden Age follower’s work, like the Large Still Life with Fruit, Beetle, and Bee, to the lush, vibrant florals of modern masters, such as the Oskar Dogarth Still Life with Flowers and Butterflies. For a touch of classical drama, explore the exquisite Italian Baroque Still Life with Peaches on a Charger. Discover the piece that speaks to your own sense of enduring beauty.